The following piece, published by BBC Culture, in 2018, feels beautifully relevant today in America, as we reel from the weight of a pandemic and of our history of racial injustice, now too public to ignore. Edisto Island, and the sea island culture around Charleston, South Carolina, has always recognized the power of black women. It is what drew me here. It in the air. It is in the sea. It is in the history.

“The US artist Theaster Gates explores the concept of the ‘Black Madonna’ in his latest exhibition, which celebrates images of powerful black women. Alastair Sooke finds out more.

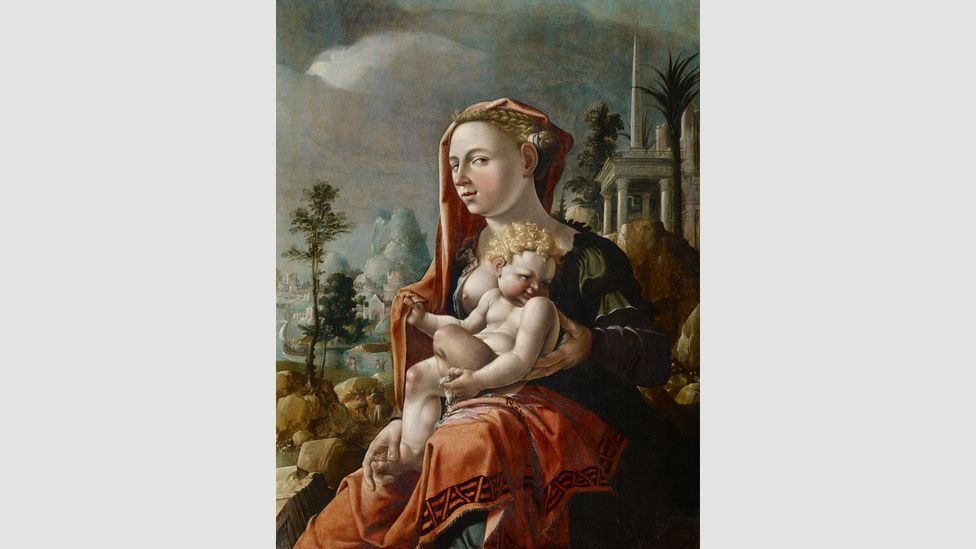

Most people coming face to face for the first time with Dutch artist Maerten van Heemskerck’s 16th-Century oil painting of the Virgin and Child, at the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland, would see a perfectly conventional picture: before an imaginary landscape meant to evoke Mediterranean antiquity, a seated blonde Mary, her plaited hair draped in orange cloth, glances at the viewer, while the Christ child fidgets on her lap, ignoring his mother’s exposed breast. So far, so traditional.

For the celebrated 44-year-old US artist Theaster Gates, however, Van Heemskerck’s painting is charged with surprising significance. “Christ has turned away from his mom’s milk, and is looking dubious and devious,” he tells BBC Culture. “Meanwhile, Mary is the image of a harlot, with come-hither eyes. I call her ‘The Ghetto Madonna’.”

Theaster Gates refers to Maerten van Heemskerck’s Virgin with Child in front of a Landscape as “The Ghetto Madonna” (Credit: Kunstmuseum Basel)

Gates’s ‘reading’ may be unorthodox, even provocative – in particular, his assertion that Van Heemskerck’s Virgin “is an octoroon, ie one-eighth black” is bound to make art historians start harrumphing. But it is typical of the way his deft mind works, making startling, unforeseen connections between disparate things.

We are standing before Van Heemskerck’s panel because Gates – who hails from Chicago and has won international acclaim for his renovations of dilapidated buildings in the city’s South Side neighbourhood – has hung it at the start of Black Madonna, his new solo exhibition at the Kunstmuseum, which will run until October. According to Gates, a thoughtful, charismatic presence who began his artistic career as a potter, the exhibition “weaves back and forth from religious adoration to political manifesto to self-empowerment to historical reflection”. It makes for a complex but intoxicating mix.

Consider, for instance, how Gates presents ‘The Ghetto Madonna’, which he calls the “anchor” of the show. It appears alongside a disturbing video, by Gates, looping clips from a 1935 film, The Littlest Rebel – in which Shirley Temple, playing the daughter of a plantation-owning family during the American Civil War, appears in blackface.

Gates began his artistic career as a potter and won international acclaim for his renovations of dilapidated buildings in Chicago’s South Side area (Credit: Kuntsmuseum Basel)

Next to this, we see a large photograph of a beautiful young black woman, her face framed by pretty, white lace, reproducing a vintage shot from a 20th-Century lifestyle magazine pitched at African-Americans. “So, here are three ‘Black Madonnas’,” Gates tells me, with a smile.

Like a virgin

The inclusion of Van Heemskerck’s painting alludes to the so-called ‘Black Madonna’ in Western art history. Conventionally, of course, Mary appears in painting and sculpture as a young mother with white skin. Sometimes, however, she appears with a dark or black face and hands – and this Black Madonna fascinates Gates, whose work interrogates the legacy of the civil-rights movement and the experience of black people in the US today.

In the past, for instance, he has made a series of artworks out of decommissioned fire hoses called In the Event of a Race Riot. Meanwhile, his show in Basel – staged across two of the museum’s venues – contains one of his dramatic black tar paintings, inspired by his father’s hard-graft work as a roofer (his mother was a schoolteacher): every aspect of the artwork, from the glossy bitumen applied with a large mop, to the copper nails used to secure the picture to its support, conforms to traditional roofing techniques. “It doesn’t leak,” says Gates, with another smile.

The exhibition has a section about the image archive of the Johnson Publishing Company (JPC), which Gates describes as an “encyclopaedia of everyday black life” (Credit: JPC)

Examples of the Black Madonna may be found all over the world. According to some estimates, there are around 500 Black Madonnas in Europe alone, mostly Byzantine icons and statues in Catholic and Orthodox countries. A monastery in the city of Czestochowa in southern Poland, for instance, contains a dark-skinned Byzantine icon of the Holy Virgin. Meanwhile, a shrine in Einsiedeln Abbey, a Benedictine monastery around 25 miles (40km) southeast of Zurich in Switzerland, boasts a miraculous Black Madonna statue, its skin possibly darkened from centuries of exposure to candle smoke. Gates has also encountered a Black Madonna in a Greek Orthodox monastery on the island of Heybeliada, near Istanbul.

I was born in a house of love surrounded by earthly Madonnas – Theaster Gates

“There are lots of stories,” says Gates, who is a professor of visual arts at the University of Chicago. He isn’t the only contemporary artist drawn to the subject: in 1996, British artist Chris Ofili painted his controversial Holy Virgin Mary, depicting a sensual black Mary in a blue robe, against an orange background, with a lump of elephant dung in place of her bare breast. “Once,” continues Gates, “there was a fire in France, and the Madonna there smote the fire, and ingested the trauma. It wasn’t that she was charred, but there was something about the trauma that made her black. I’m curious about this idea: could a ‘Black Madonna’ simply be a white Madonna with trauma? In other words, do Madonnas ‘mature’ towards blackness because of something bad happening?”

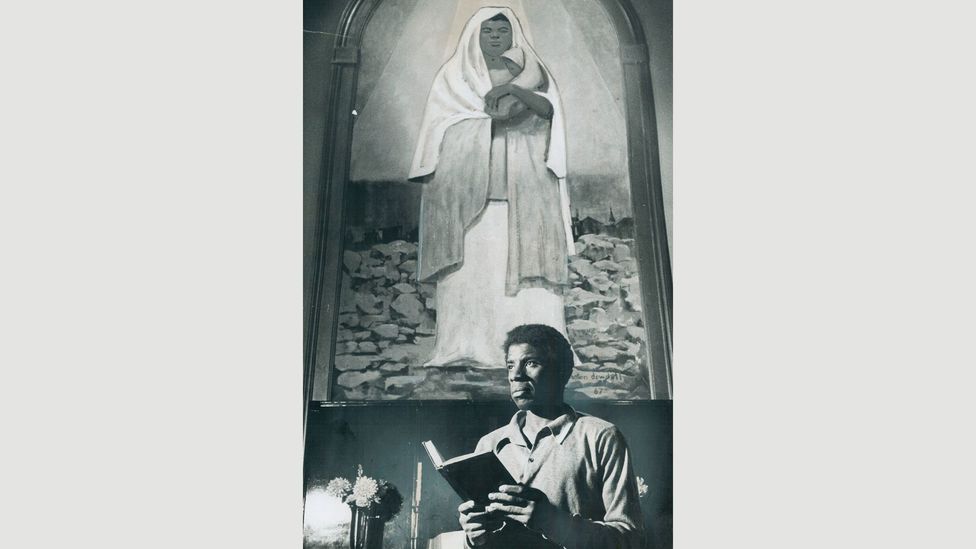

A black Madonna is shown behind Beverly Williamson, caretaker of the Central United Church of Christ in Detroit (Credit: Getty Images)

It’s an intriguing, unsettling notion – but, says Gates, who has two degrees in urban planning, he isn’t interested in the ‘history’ of the Black Madonna so much as the “lived experience of those who worship her”. “I got super-curious about [Our Lady of] Guadalupe,” he says, referring to a famous full-length representation of a mixed-race Mary in a shrine in Mexico City. He also set out to discover more about Yemoja, a Yoruba deity sometimes viewed as an equivalent of the Virgin Mary, and “the role of the black woman in Haitian voodoo”.

‘Beautiful, powerful women’

Gates says that his interest in the Black Madonna stems from his experiences growing up. He was raised in a Christian household, the youngest of nine children, and the only boy. “I was born in a house of love,” he tells me, “surrounded by earthly Madonnas.”

Aged 13, Gates became director of the youth choir at his church. Is he still a believer? He pauses before replying: “I definitely have a stronger belief capacity than most, as a result of having been brought up religious.” He no longer attends church every Sunday, he says, but he does have a gospel-inspired band called the Black Monks of Mississippi (who performed in Basel to mark the opening of his new show). “Having the capacity to believe in things is what artists do,” Gates tells me. “Like, I believe that the ugly can be beautiful. I have an amazing belief muscle.”

Sometimes I wonder: if women had the position they deserved [in society], would things be the same? – Theaster Gates

When he was 19 years old, Gates visited relatives in Detroit, where he came across the Shrine of the Black Madonna – a church once described by The New York Times as “an important centre for black theology and political power”. It was founded in 1967, in the wake of the decade’s urban race riots, by the religious leader Albert Cleage. “The proposition,” explains Gates, “was that the mother of God was black, therefore Christ was black, and so we were connected to this long lineage of powerful people.” As a teenager, Gates found this idea exciting. “It was very radical,” he says.

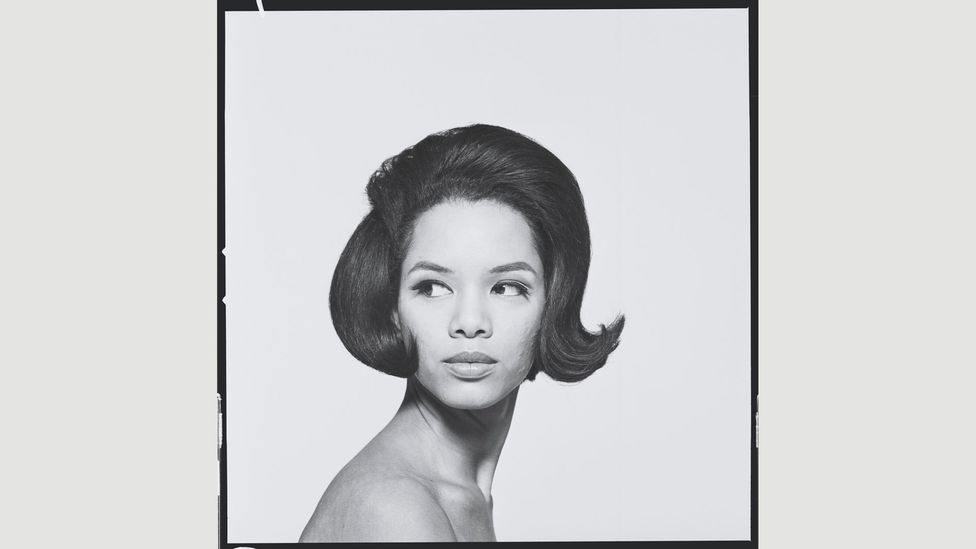

This image of the musician Corinne Bailey Rae represents Gates’s aim to celebrate ‘beautiful powerful women’ in the exhibition (Credit: David Sampson / Courtesy of Theaster Gates)

Another important, related strand of Gates’s Black Madonna exhibition concerns the photographic archive of the Johnson Publishing Company (JPC), which, since 1945, has published the monthly magazine Ebony, conceived as an equivalent of Life magazine for an African-American market. Gates says that copies of Ebony and its sister magazine Jet, modelled on Reader’s Digest, could be found “all over my house” when he was growing up: “They were a kind of encyclopaedia of everyday black life.”

At the Kunstmuseum Basel, Gates has constructed an elegant, saltire-shaped wooden cabinet containing more than 2,600 images of black women from the archives of JPC, which the artist describes as “the most important black publishing company to have ever existed”. Many of the images present beautiful models dressed in glamorous clothes – but there are also photographs of ‘ordinary’ women engaged in domestic activities such as cooking or looking after children.

“I wanted to celebrate black female images in the collection,” explains Gates, who considers the “beautiful, powerful women” who appear in the cabinet as ‘Black Madonnas’, ie “everyday women who do miraculous things”. “At the heart of it,” he continues, “I was super-interested in how powerful women in and around my life seem to be a solution that the world is never looking for.”

This, says Gates, is the nub of his new exhibition. “So many of the challenges in this world are brought on by men,” he tells me. “Sometimes I wonder: if women had the position they deserved [in society], would things be the same? Would we be as greedy, as corrupt, as non-caring, as warring? Those are the questions on my mind.”

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180719-the-intriguing-history-of-the-black-madonna

Leave a comment